It was only following the appointment of Joshua Seufert in 2012 that I was able to devote all my time to the Bodleian Library’s so-called “special” collections of Chinese materials; before that I worked mostly on acquiring modern materials, both printed and later electronic. Our principal supplier was CIBTC (China International Book Trading Corporation 中国国际图书贸易集团公司), who hosted most of my visits to China.

I was usually looked after by Wang Tong 汪彤 and later Zhu Min 朱敏, who both developed a very good sense of what interested me, and took me to places that would have been inaccessible without their help. I can’t thank them enough for their hospitality over the years, and for showing me some of the most beautiful and impressive sights that I’ve ever seen.

A particularly memorable trip was the one I made in April 2006, which included a visit to Wenwu Chubanshe 文物出版社 in the centre of Beijing. There I saw what I was told was the last remaining printing operation within the walls, a collotype process using a rather old machine.

Here is the complete collection of the pictures that I took on the day of my visit, Tuesday 25 April 2006.

I don’t know what was being printed when I took these pictures, but clearly it is calligraphy and is nothing more than solid black ink on white paper. The same goes for a Buddhist scripture that had been printed on the press earlier in the year for a temple in Tianjin, of which I was given a copy as a memento. I subsequently gave it to the Bodleian and catalogued it as follows:

妙法蓮華經觀世音菩薩普門品 一卷 / (姚秦釋)鳩摩羅什譯

2006年北京文物出版社珂羅版印本

線裝1冊 : 圖 ; 34公分

天津大悲禪院敬印

Sinica 6004

A few more specimen pages 書影 from this edition are attached to its record in the Serica Project.

These pictures have led me to take another look at collotype printing, of which there are some classic examples in the Bodleian collection. I’m ashamed to admit that when I first catalogued them, I dismissed them as nothing more than early versions of what I was currently acquiring in spades: photolithographic reproductions of Chinese editions, many of them illustrated.

I will not pretend to understand the process of collotype printing in any detail. There is an excellent Wikipedia entry on the subject, and it is adequately summarised in the opening words of T.A. Wilson’s book The practice of collotype (1935):

“The collotype process is a photo-mechanical method of printing with ink from the plane surface of a photographic film. It is a process which is capable of producing prints of great beauty, prints that are soft in tone, continuous in gradation, and with remarkable definition of detail. The process combines the arts of photography, printing, and coloring, and provided that a suitable negative be made, any subject can be rendered in collotype. The plates may be printed in a hand press, where the manipulations are extremely variable, or in a power machine, where the dampening, inking, and printing are more or less automatic. The rate of printing of the best collotypes is slow, generally under 500 impressions an hour.” [1]

And in the short account of collotype in his book The technique of prints and art reproduction processes, Jan Poortenaar makes the point that “collotype is unequalled, save by hand-photogravure, among all the photo-mechanical processes for high-class reproduction-work.” [2]

From this it is clear that the examples being printed in Beijing at the time of my visit did not represent the full capabilities of collotype printing. And it is equally clear that when I catalogued two of the earliest Chinese collotype editions in the Bodleian Library, I completely failed to notice how remarkable they were. These two editions are treated in extensive detail by Cheng-hua Wang (Professor of Art and Archaeology at Princeton) in her article New printing technology and heritage preservation: collotype reproduction of antiquities in modern China, circa 1908-1917.

Both were published serially in Shanghai beginning in 1908.

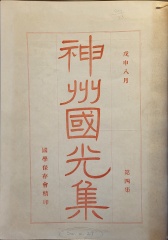

The Bodleian only has a single issue of the first one, Shenzhou guoguang ji, published by Deng Shi 鄧實 (1877-1951):

神州國光集 : 存第四集

清光緒戊申[1908]國學保存會珂羅版印本

洋裝(原平裝)1冊 : 圖 ; 31公分

Sinica 6848

But the Library has rather more of the second one, Zhongguo minghua, published by Di Baoxian 狄葆賢 (1873-1941):

中國名畫. 第一~二十八集 / (民國)美術研究會審定

民國上海有正書局珂羅版印本

木匣1盒(線裝28冊) : 圖 ; 38公分

Sinica 3973

Backhouse 719 存第一~十集. – 線裝10冊 ; 39公分

Sinica 6370 存第二﹑八﹑十集. -線裝3冊 ; 39公分

More illustrations from this work are attached to its record in the Serica Project. And sixteen issues of Zhongguo minghua are in the possession of a French collector who has not only reproduced all the illustrations from them, but has also presented a comprehensive and detailed account of the publication and its background.

The set in the Fung Ping Shan Library in Hong Kong has 40 issues, and is complete. The first copy in the Bodleian (Sinica 3973) preserves a set of the first 28 issues. It is contained in a wooden box (of which there are very few examples in the Bodleian) which suggests that the vendor or owner considered it to be both complete and valuable. Print runs were rather short – Poortenaar says (p.147): “Five hundred good prints may perhaps be obtained; some people speak of a thousand, but then the question arises what are good prints, and what are not.” So to satisfy demand each issue was reprinted many times. Actually these are not strictly reprints, but re-editions, as a comparison of the Bodleian copies will confirm; and in any case, I don’t think storing gelatinous collotype plates and reprinting from them is feasible. Sinica 3973 appears to have been put together in the mid-1920s from copies which had run to as many as 12 editions – here are the details.

It’s always good to discover “landmark” editions in the Library’s collections, and I never expected these two collotype publications to fall into that category. But they do. Professor Wang explains how for the first time they showed to the general public artworks that hitherto had only been available to a privileged few, leading directly to a discussion of what constituted the Chinese national art heritage and how it might be preserved, which was precisely the intention of their publishers, Deng Shi and Di Baoxian.

2. Poortenaar, Jan: The technique of prints and art reproduction processes (London: The Bodley Head, 1933), 146.

Leave a comment