When I made my first posting to this blog in November 2011, I described it as the waizhuan 外傳 (“outer chapter”) to the neizhuan 內傳 (“inner chapter”) of the Serica Project, whose aim was to locate, identify, and list all the pre-modern Chinese materials in the Bodleian and other Oxford libraries; it was designed to answer the question that library catalogues can’t, that is, what have you got. (The “inner chapters” in Chinese thinking are the official, orthodox accounts; the “outer chapters” are where writers express their own freer accounts, untrammelled by convention.)

At an early stage of the project the Library offered to host the blog on its own server. I declined the invitation for reasons which will soon become apparent.

The Serica Project: its current state

The Serica Project had been primed by a generous donation from Nicholas Coulson, following which further substantial funding was obtained from the Tan Chin Tuan foundation in Singapore. By the time of my dismissal at the end of September 2017, although I had not only fulfilled but substantially exceeded what had been required of me under the terms of the funding, much work remained to be done. So in time-honoured fashion I continued to work on my project in retirement. Between then and the time the allegro catalogue was closed at the end of February 2020, I had added a further 6376 records to the database, mostly the contents of the collectanea (congshu 叢書) that Joshua Seufert had transferred from the China Centre Library before going to Princeton in 2018.

What I had failed to realise is that times had changed. Working on the Library’s collections in retirement was now not only discouraged, but was soon not even to be tolerated. My first intimation of this came from Bodley’s Librarian’s deputy, now in charge of her own university library, who told me to forget everything I ever knew about my subject and spend more time with my grandchildren. I got the impression that she considered a librarian whose interest in his work persisted after he ceased to be paid for it must be mentally ill.

The final blow came in November 2021, when the Library suspended the updating of the Serica database without a word of warning or explanation either to me, the wider academic community, or the donors. I simply discovered one day that I could no longer upload a quantity of new work. My access to the server had been terminated.

The Serica database however continued to be accessible on the Library’s website until last month (October 2024), but only as a crippled relic of its former self: incomplete, occasionally inaccurate, and failing to give access to everything that has now been digitised. Moreover, the specimen pages (shuying 書影), invaluable to Chinese bibliographers and numbering several thousand, had for some reason been discarded in their entirety.

One wonders what sort of library it is that receives over a quarter of a million pounds to set up a bibliographical research tool one minute, and then trashes it the next.

Fortunately, I had long been acting on the advice of a colleague to download everything I could from the servers to which I had access before I became the inevitable victim of managerial high-handedness. This I did regularly, backing up my work after every session, so that with my limited programming knowledge I have been able to recreate a simplified but workable version of Serica and its infrastructure on my own server, which is now safely out of harm’s way. I’m thus able to continue working towards the completion of the project (and in doing so, honour the generosity of the donors), and this account of the Bodleian’s collection of Chinese Bibles is another step on the way.

The Bodleian’s Chinese Bible collection

Until I completed my listing of our Bibles just over a year ago, I had only catalogued the editions with Sinica shelfmarks. I had lost sight of more than two hundred editions in the Library’s classified collection, which was the work of Edward Williams Byron Nicholson (1849-1912) who was Bodley’s Librarian from 1882 until his death in 1912. [1]

Nicholson devised his classification during the very first year of his appointment, and it was implemented immediately in 1883. His scheme was numerical, and evolved from earlier schemes that had been in use in the Library since the time of its foundation. [2] Although it remained in use for over a century, it is surprisingly ill documented. The fullest description known to me is that of Michael Heaney [3], but Heaney makes no mention of the non-numerical part of the scheme which was used for Oriental materials (shelfmarked Arab., Chin., Heb., Jap., &c.), nor the shelfmarks used for the classification of Judaeo-Christian scriptures (Bib., O.T., N.T., Ps., followed by a language designation). Both the numerical and non-numerical designations in Nicholson’s scheme are followed by a letter denoting the physical height of the item (to make the most economical use of shelfspace), and then a running number. It is worth noting that when the New Library was built in the 1930s, the shelving was designed to accommodate this sizing.

The Bibles in the Sinica collection are for the most part those that were acquired before the inception of the Nicholson classification in 1883. There are 121 editions, most of which are not complete Bibles, but single books or groups of books.

The Bibles acquired after 1883 were given Nicholson shelfmarks as listed here. There are 228 editions. Working from the handlists, just over a year ago I was able to take stock of everything we have, and to catalogue it.

There are a further 33 editions in Regents Park College, so that in total I have so far discovered 333 different Chinese editions of the Bible (or parts of it) of in Oxford libraries. There are listed here, as well as under their classified place in the Serica website (西人著書 耶穌教 聖書). Inevitably there is some duplication, so that the number of copies is rather higher. Also, it is quite likely that more Bibles will be found in other Oxford libraries.

Other collections

The largest collection of Bibles in the world is believed to be that of the Bible Society (formerly known as the British and Foreign Bible Society) which was transferred to Cambridge University Library when the Society sold its premises in central London (146 Queen Victoria Street) in 1985. I referred to this in an earlier blog entry which has some relevance here. When the collection was catalogued by Darlow and Moule in 1911, it contained 568 Chinese editions, numbered 2452-3019. [4] By 1975 the collection had grown to over one thousand editions, and was the subject of a second printed catalogue compiled by Hubert Spillett [5], who had worked for the Baptist Missionary Society from 1930 until his retirement in 1967. Spillett re-numbered the Bibles 1-1091, 1-568 being Darlow & Moule’s 2452-3019. The collection is now listed online here.

Of course there was already a collection of Chinese Bibles in Cambridge before the acquisition of the Bible Society’s library, but it was small, numbering only 64 editions. Yan He, the Library’s Chinese specialist, has very kindly sent me a list of them.

Clearly the Cambridge collection is by far the larger, and may possibly be the largest collection of Chinese Bibles in existence. But this is mostly because it contains a much greater number of twentieth-century editions. For the study of Chinese Bible translation in its nineteenth-century heyday, the Oxford and Cambridge collections are of similar size and value.

Many of the Bibles in both the Oxford and Cambridge collections came from two of the great nineteenth-century international exhibitions: the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia (these books probably reached us through the agency of Alexander Wylie), and the International Health Exhibition of 1884 in London. I discussed this matter in some detail in a paper I presented in 1988 at a conference in Taipei, and have just revised it, mostly because of its relevance to this blog entry. It can be seen here.

Cataloguing

Spillett’s catalogue follows the pattern of Darlow & Moule’s, and is descriptive. My list conforms with standard library cataloguing rules, where possible reproducing bibliographic information as it appears on the book, and expressed in ISBD (International Standard Book Description) format. Here are examples of the same entry from each of the catalogues:

A few words of explanation are necessary.

I have used the headings and filing order of the two Bible Society catalogues, so that the word “Bible” (not necessary in their case, as the catalogues are of Bibles only) is followed by the language (usually called “dialects” in Chinese, even when they are mutually unintelligible), then the date, then the part of the Bible where necessary: it usually is, as most editions are not of complete Bibles. I have used the 19th-century spellings of the dialects and place names (Foochow, Amoy, &c) not out of antiquarianism, but to be consistent with the two existing published catalogues and the usage in all contemporary documentation.

The Bibles, like all the other missionary publications, present cataloguing problems as they are neither Chinese nor English, but hybrid in both form and content. Unlike traditional Chinese publications, in which what appear to be title-pages are no such thing (see section 3 of this blog entry), in the missionary publications, which were written and printed by foreigners, they really are title-pages of the western type and as such are what cataloguers call the “principal source of information”. And as the publications are usually more western than Chinese in presentation, I have expressed the imprints not as a single sentence of classical Chinese, but with the more familiar ISBD punctuation: “place : publisher, date”. Also, the cataloguing language in the Serica Project is Chinese, but again the normal rules simply can’t be applied. Just as the English translation of the note 「版心題名《舊約全書》」 is long and inelegant, so the English “2 Samuel, tr. by S F Woodin” makes little sense in Chinese except to the initiate. So my cataloguing language is mixed.

And when noting the version of the Bibles, if the names of the translators don’t appear on the publication, which is usually the case, I’ve reproduced the information given by Spillett uncritically, having neither the energy, the ability, or the means to work it out for myself. In the case of romanised translations, I’ve ignored the accents altogether, as some of them are so bizarre that I doubt if they’re even encoded.

My records are therefore a bit of a mess, and I don’t know what to do about it. At least they’re better than nothing. It has taken nearly 150 years to get this far; perhaps it will take another 150 years for the Library to do the job properly. As things are, the only way to find out what we’ve got is to look at my list.

A few bright spots

Cataloguing our Bibles was on the whole a rather boring task, but during the course of the work, there were a few bright spots. Here are some of them.

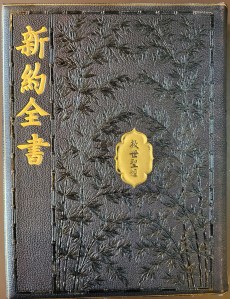

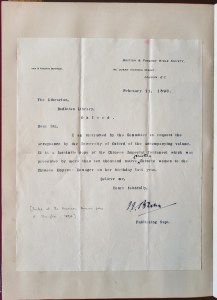

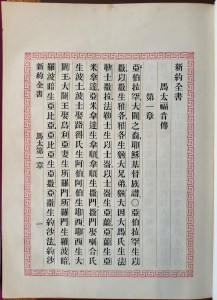

This is perhaps the most luxurious Chinese edition of the Bible ever produced. It is the New Testament which as the accompanying letter explains was presented to the Empress Dowager on the occasion of her birthday by a group of over 10,000 Chinese Christian women in 1894:

John Lai was a doctoral student in Oxford in the earlier years of my curatorship and now has a chair in the Chinese University of Hong Kong and is an authority on Chinese missionary translation work. He has confirmed my suspicion that the scriptures which the missionaries translated into Chinese dialects, usually in romanisation, are almost certainly the most substantial, if not the only examples we have of these dialects as spoken in previous centuries.

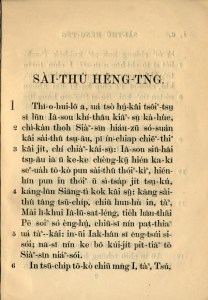

This is a translation of the Acts into the dialect of Swatow (Shantou 汕頭), a coastal city at the eastern end of Guangdong Province, typeset and published in 1889:

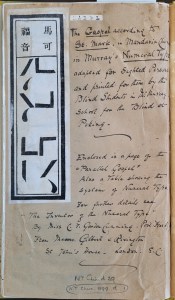

William H Murray (1843-1911), deeply moved by the fate of the blind in China, developed a Braille system based on numerals which enabled blind people to learn to read in a matter of weeks and used it to produce Bibles, hymnals, and other books.

This edition of Mark published in 1896 is a representation of his system in print – I don’t know if it’s a unique example, or whether there are other editions of this kind; I think the phenonemon deserves its own study:

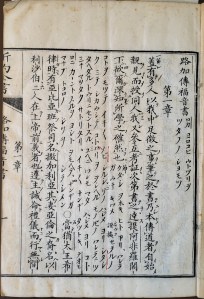

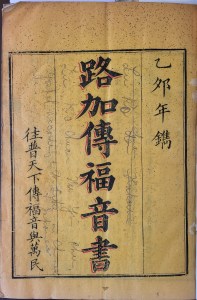

Finally, this very interesting edition came to light as I was going through the collection. It isn’t Chinese, and is an example of how Library books in non-roman scripts were often inappropriately shelfmarked so that they lay unnoticed and unidentified, sometimes getting lost for centuries. It’s actually in Japanese, but has a Chinese shelfmark. It’s a translation of St Luke’s gospel by Bernard Jean Bettelheim (1811-1869) which was blockcut in 1855. The text is in kambun 漢文, and each section is followed by a translation into Japanese expressed in katakana カタカナ:

2. Wheeler, George William: Bodleian press-marks in relation to classification. Bodleian quarterly record 1:10 (1916), 280-292; 1:11 (1916), 311-322.

3. Heaney, Michael: The Bodleian classification of books. Journal of librarianship and information science 10:4 (1978), 274-282.

4. Darlow, T.H. & Moule, H.F.: Historical catalogue of the printed editions of Holy Scripture in the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society. Vol.II, Polyglots and languages other than English. London: Bible House, 1911.

5. Spillet, William Hubert: A catalogue of scriptures in the languages of China and the Republic of China. London: British and Foreign Bible Society, 1975.