This is my eleventh blog entry on the subject of the Chinese books that came to Europe in the 17th century. I have now tagged them all as “17th century accessions” (in the “Categories” list at the bottom left of the screen) so that they can be conveniently located. As indicated in my last entry on this subject, which I’m astonished to see was written over four years ago, if I can I like to say more about them than it would be appropriate to put in my simple list. And as in this entry, that often amounts to little more than repeating what others have told me.

Two recent finds are of unusual interest, and both involve Stuttgart in one way or another. I will deal with them separately in this and my next blog entry.

When books that came to Europe in the seventeenth century are discovered, they are usually found in older libraries where they have often lain unidentified for centuries, or in newer libraries that house older collections. Of all the places that one might look for them, China would be the last.

Yet the latest discovery was indeed made in China. It was brought to my attention by Zheng Cheng, who e-mailed me in August last year to say that while reading an issue of Huaxi yuwen xuekan 华西语文学刊 he had come across an article by the scholar Ai Junchuan 艾俊川 in which he reproduces, with a very informative introduction, 23 half-leaves from an edition of the Shuihuzhuan 水滸傳 which he bought from an English dealer on eBay in December 2007 for the sum of £26. [1]

In his article, Ai establishes that the half-leaves in his possession are not only from the same edition, but from the same copy of the well-known fragments preserved elsewhere, as documented in my list. It is extraordinary that this is the second fragement of that copy to have been found on eBay – I documented the discovery of the earlier, much larger one in my blog entry of November 2020.

Furthermore, Ai has also established that they dovetail precisely with not only the missing leaves, but also the missing half-leaves of the Stuttgart fragment. Unfortunately owing to the trimming, the pagination of these half-leaves is missing, but on the basis of their content, it should be possible for someone with a detailed knowledge of the Shuihu text to figure it out.

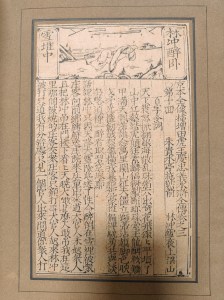

The reason why I’m referring to “half-leaves” is because a previous owner has cut the two panels of text out of each leaf (sacrificing the banxin 版心 in the process), and mounted them individually as shown in this image, which Ai Junchuan has very kindly sent me:

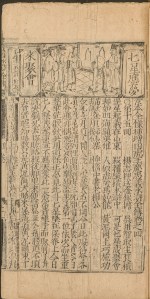

This is the first half-leaf of juan 卷 3; for comparison, here is the first half-leaf of juan 卷 4 in the Stuttgart copy:

Although I first encountered the single leaf preserved in the Bodleian (Sinica 121) almost fifty years ago, I never took the trouble to find out exactly what it is, and why it is significant. In fact I didn’t even know that there is no standard version of the Shuihuzhuan despite its status as one of the “four great works” 四大名著 of Chinese fiction.

Ma Youyuan 馬幼垣 has written two lengthy monographs on its extraordinarly complicated textual history [2]. There are many quite different versions which fall into two groups, “complex” 繁 and “simple” 簡; the “simple” versions narrate the events in less detail, and are intended for less sophisticated readers. And whether simple or complex, some editions may be “augmented by the insertion of the tales of Tian Hu and Wang Qing” 插增田虎王慶.

As indicated by its title 《新刻京本全像插增田虎王慶忠義水滸全傳》 the European fragments are from a copy of the “augmented” version, which is also “simple”. In fact it is believed to be the earliest extant example of such an edition.

2. 水滸論衡 (台北: 聯經出版事業公司, 1992, ISBN 957-08-0794-6); 水滸二論 (台北: 聯經出版事業公司, 2005, ISBN 957-08-2887-0).

Leave a comment