I’m not sure if it’s good (or at least acceptable) practice to rename and rewrite blog entries that have already been published, but I’ve just done so. So much information about the Stuttgart calendar came to light following my original posting that I’ve decided to rewrite my account of it and give it its own new entry, removing it from my previous entry which is now only concerned with the recently discovered Shuihu fragment.

The story began in November 2023, when Marcel Thoms, Head of Acquisitions & Cataloguing at the Württembergische Landesbibliothek told me about a calendar that had been discovered by accident while the Library was preparing an exhibition on time division. Although there is no absolute guarantee that the calendar came to Europe in the 17th century, in its subject matter and physical appearance it is of a piece with the rest of what I call the “seventeenth-century corpus”, and Marcel has told me that its shelfmark (Cod. or. 4° 4, especially the low number 4), indicates that it was part of the founding collection of the Library’s predecessor, the Herzogliche Öffentliche Bibliothek. This had been founded in Ludwigsburg in 1765 by Duke Carl Eugen (and most unusually it was open to the public from the start, as its name suggests). At that time it would have been quite normal for figures such as Duke Carl to have possessed a fragment of one of the Chinese books that came to Europe in the 17th century, as a glance at my list will confirm.

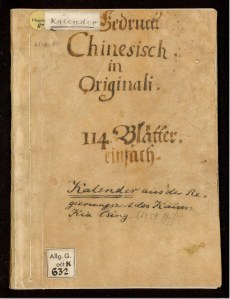

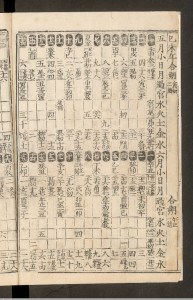

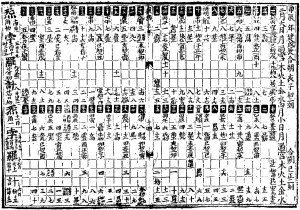

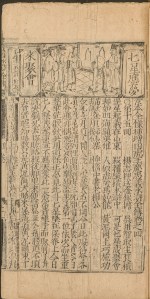

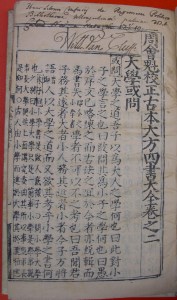

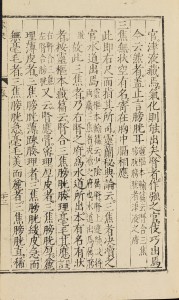

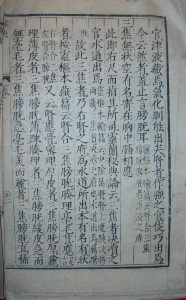

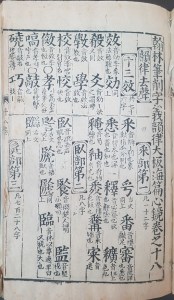

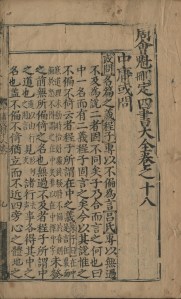

The Stuttgart volume is only a fragment of the complete work, whose full extent is unknown. The surviving leaves are all from juan 卷 7: 2-60上 (the first and last of these leaves are badly damaged in the area of the banxin 版心) and cover the years 1559-1568 (嘉靖己未年一、二月~嘉靖戊辰年三、四月). Here is the front cover and a specimen page from the calendar, which has been digitised:

I had no clear idea of why calendars of the lucky days in years gone by should have been published, so again I went to my friend Zheng Cheng 郑诚, who as expected told me exactly why. They were produced to enable fortune-tellers to calculate the best date for marriages, funerals, or other important events on the basis of the subjects’ birthday information; that is, their shengchen bazi 生辰八字, or “eight birthday characters”, namely the year, month, date, and hour of their birth each expressed in two characters from the sexagenary “heavenly stems and branches” (干支) system. Although people would remember these dates, they would not know the astrological details associated with them.

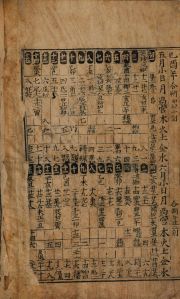

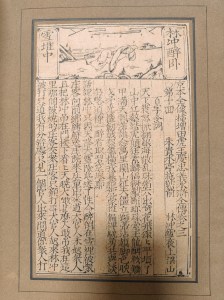

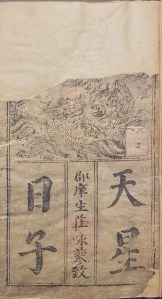

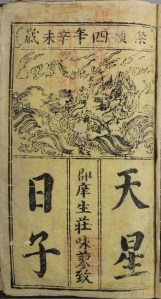

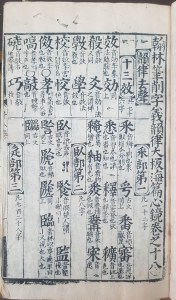

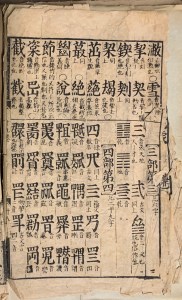

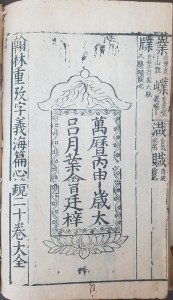

Pursuing his enquiries, Zheng Cheng got in touch with the scholar Zhao Jianghong 赵江红 who has written a number of articles on the subject, and she informed him that there is another fragment of the same copy of this calendar in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (shelfmarked Sin 133-C ALT SIN). This fragment has also been digitised. It contains most of juan 卷 6 (unfortunately the pagination is not visible in the digitisation) covering the years 1549-1558 (嘉靖己酉年五、六月~嘉靖戊午年十二月), and most importantly the first half-leaf of juan 卷 7, which is missing in the Stuttgart fragment.

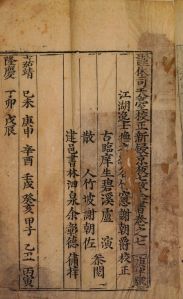

Not only does this indicate that the Vienna and Stuttgart fragments are consecutive parts of the same copy, but it also provides us with an exact title for the work as well as other bibliographical details.

So the title of the work is 《謹依司天臺校正新鋟京板七政全書》 jin yi si tian tai jiao zheng xin qin jing ban qi zheng quan shu, and it was edited by 謝朝爵 Xie Chaojue and published by 余彰德 Yu Zhangde, a member of the famous Yu family of Jianyang 建陽 publishers, making the edition of a piece with other parts if the 17th century European corpus.

When I originally posted my account of this calendar I had already learned from Zheng Cheng that the qizheng 七政 referred to in the title are the “seven ruling powers” (for want of a better translation) of the Sun, Moon, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, and Saturn, which are all used in astrology and prognostication. But I had no idea of how the calendar was structured until Edward White posted a very informative comment, as follows:

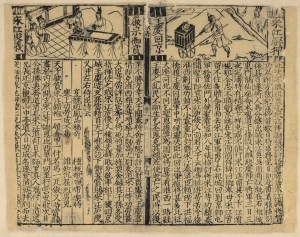

“The page of the Stuttgart calendar you showed [and presumably this also applies to the page from the Vienna fragment] is a tabulation of the places of the planets in the sky. The top half of the page shows the data for the 6th month, and the bottom for the 7th. Each column represents a day of the month, and each row shows (from top to bottom):

1- The date of the month (in white on black lettering)

2- The sexagenary cycle of the day

3- The sun’s position

4- The moon’s position

5- The time of day the moon changes zodiac sign

6- Jupiter’s position: (水 is probably an error for 木)

7- Mars’ position (Mars seems to be in retrograde motion in this period, that’s why the numbers go backwards)

8- Saturn’s position

9- Venus’ position

10-Mercury’s position

All the positions from 3-10 (except 4) are stated in terms of the 28 lunar mansions or 宿. Additionally, it seems publishers only noted the days when the planet moved a degree and did not provide entries for the intermediate days. This is especially apparent in the rows of the slow-moving planets Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.”

In a subsequent e-mail message, Edward also points out that in addition to the “Seven Governors” 七政, the almanac also tabulates the “Four Remainders” 四餘. These are four mathematically determined points which are also considered significant in astrology: Ziqi 紫炁, Yuebei 月孛, Rahu 羅㬋 and Ketu 計都, the last two being adapted from Indian astrology. The positions of these points are tabulated in the final columns of each month in both the Stuttgart and Vienna fragments; their names are abbreviated to 炁、孛、羅、計.

Zheng Cheng has located a few similar calendars in Japan, one in the Fu Ssu-nian Library 傅斯年圖書館 in Taipei, and one in the Palace Museum Library in Beijing. This last one is presented in almost exactly the same format as the Stuttgart edition, and has been reproduced twice:

1. 续修四库全书, 第1040册 (上海: 上海古籍出版社, [1996])

2. 故宫珍本丛刊, 第388册 (海口: 海南出版社, 2000)

Both the Palace Museum edition and all the others have later date ranges than the edition in Vienna and Stuttgart, which might well be the earliest in existence.

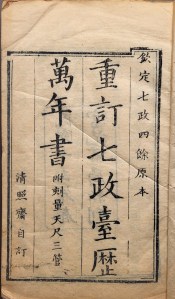

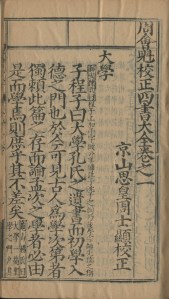

There are later, even relatively modern examples of this type of calendar, and there is one in the Bodleian which I bought in Yamada Shoten in Tokyo in 1981:

重訂七政臺歷萬年書 : 不分卷 / (清)欽天監修

民國十二年[1923]富記書局刊本

線裝1冊 ; 25公分

同治十三年甲戌[1874]至光緒三十四年戊申[1908]

Sinica 2666

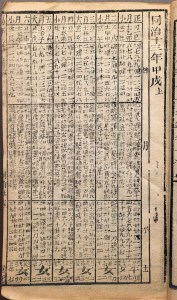

Of this, Edward White says:

“The 重訂七政臺歷萬年書 is published in an even more compact format. In the case of the Sun, Moon and Mercury The publishers dispensed with numbering the days individually, and instead formatted the entries for each month as a 10×3 grid; the reader was expected to find the relevant data for a given date based on its position in the grid. (eg: the 5th box of the right column of the grid = 5th day of the month). The bottommost row shows the dates Saturn changes degree.

I should also note that some modern Chinese almanacs still publish the planetary coordinates: Examples include 正福堂、繼福堂、真步堂.”