Work on my project, and indeed everything else, was suspended for the second week of July while I attended the funeral of my mother-in-law in Japan. There are already one or two English accounts of Japanese funerals on the internet, but there is no harm in offering a different perspective, and my observations are both fresh and close, so I wrote down my recollections of the event with my netbook on the flight home last week (netbooks are perfect in the cramped conditions of economy class), and published them in my blog as soon as I returned.

I have now removed my account from the blog entry itself (but it is still visible here), as I felt not so much that the account was off-message (although it was), but that it was destroying the blog’s proportions and elegance. Removing it also helps to emphasise the fact, as if any emphasis were needed, that whatever is found on the internet is evanescent, and that the only way to time-proof it is to print it out.

At the funeral in Japan, while the Buddhist priest performed the rites, seeing him read sacred texts caused my mind to wander to our old Chinese books, and in particular to the scriptures and rituals of Buddhism and Daoism. These are well-represented in the Bodleian and other western libraries, for the simple reason that they were readily available to early western visitors to China, whereas the more respectable editions of the scholarly class and the imperial government were not. Conversely, owing to their lack of respectability, religious texts such as those that would have been used in a local temple are not commonly found in Chinese libraries.

Andrew West, in his masterly Catalogue of the Morrison Collection of Chinese Books (London, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1998), puts it thus (p.xvi): “[Morrison] … bought whatever books were available and affordable, with the result that the majority of books in his collection were the output of the contemporary publishing industry. These were precisely the books that Chinese collectors did not deign to collect, and hence which today are often more difficult to locate than ‘rare’ Ming editions.”

Furthermore, of the 893 records in the Morrison catalogue, 212 – approaching a quarter – are Buddhist and Daoist works (pp.169-237). The author’s classification and explanation of these texts in particular are essential reading for those who like me are attempting to document their own collections, as they are among the most difficult to comprehend.

There are two reasons for this difficulty. The first is linguistic, but as in other subject areas, the technical vocabulary of Buddhism and Daoism although large is limited, and with application can easily be learned, even if the precise meaning of the concepts they express is elusive; the second is more serious, as it concerns the book as an object, and how it was used.

The following richly illustrated Buddhist work in the Bodleian collection is one of the best of its kind, and is a case in point. I bought it from Han-Shan Tang (London) in 2003, and have not found it in any other library, whether Chinese or western:

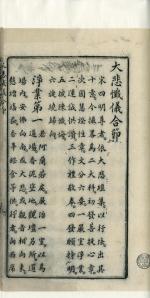

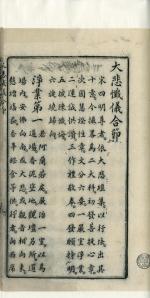

大悲懺儀合節 一卷. 附 大悲經咒繪像 一卷. 大悲出真言 一卷

清中葉後期(?)刊本

板存成都文殊院

線裝2冊 : 圖 ; 32公分

Sinica 4015

According to the colophon, the owner of the blocks was the Wenshuyuan temple in Chengdu. This temple was founded in the Tang dynasty, and is still in existence; it is the best preserved temple in Chengdu, and a major tourist attraction. Most likely the Wenshuyuan was also responsible for cutting the blocks, and before that, assembling and editing the text. I have guessed the date on the basis of the book’s appearance – there is no date anywhere in the text, and there is no preface.

In Oxford, this book is far removed from its context. To know how it was used we would have to be present among the clergy and congregation of the Wenshuyuan at the time it was produced, just as I was at the Japanese funeral. There, I saw the large folded sheet from which the priest read out the canonical name of the deceased, so that if I found such a document in our collection, I would now know not only what the text was, but also exactly why the document was produced and how it was handled at the ceremony.

In the case of Sinica 4015, I can only attempt to explain its contents. I have no idea how it was distributed (was it sold, or was it for free distribution?); to whom it was distributed (everyone, or just the clergy?); or how it was used (like a Christian missal at a religious ceremony, or for private study in preparation for the ceremony?).

Sinica 4015 has been restored in jinxiangyu 金鑲玉 format, and is now presented in two volumes, containing three different and separately paginated sections. However, the title on the first leaf of one of the volumes has left an impression on the blank final half-leaf of the other volume, so that we know not only that the two volumes were originally bound together, but also in what order. Restored books are often interleaved, as here, with the result that their volume is doubled, so that in catalogues, even greatly different volume counts of the same title cannot be taken to indicate different editions.

The work’s three sections are presented in this order:

1. 大悲經咒繪像. 45 leaves.

2. 大悲出真言. 22 leaves.

3. 大悲懺儀合節. 20 leaves.

The main section

This order notwithstanding (works described as “appended” 附 in Chinese bibliography often precede rather than follow the main title), I consider the third section to be the main title in this edition, on account of both its content and its presentation: it is the only one to have its title presented at the beginning and end of the text in the conventional way (《大悲懺儀合節》 at the beginning and 《千手眼大悲心咒行法懺儀》 at the end), and the only one to have its title in the banxin 版心 of each leaf; the banxin of other two sections are completely blank. Also, the only evidence of the edition is found on the final page of this section (illustrated above, together with the first page). The text has six parts, and describes how to perform the Guanyin “confessional” ritual; chan 懺, from the Sanskrit kṣamayati, is defined by Soothill as “to ask pardon” (p.478). This includes a recitation of the all-powerful Dabeizhou 大悲咒, or Dhāranī of Great Compassion, the most powerful means of invoking the deity. The six sections are (1)淨業 (2)供讚 (3)禮敬 (4)持明 (5)懺悔 and (6)歸向, and I am leaving it to others to provide a detailed account of them.

The first appendix

The edition opens with the first of the two “appended” works, which is an illustrated exposition of the text of the Dabeizhou. The pietistic writer John Blofeld has said of it: “So powerful is this dhāranī, especially when recited under such circumstances as those I am describing [at an annual Guanyin ritual in a large temple on the coast near Amoy], that one’s consciousness, borne aloft by the flow of mantric sound, soars upwards to a sphere of marvellous luminosity”. (Bodhisattva of Compassion, 1977, p.109). The mantra was translated into Chinese in the Tang dynasty from the Sanskrit, which is now lost, so that the current Sanskrit text has been reconstructed in modern times from the Chinese. The words are apparently meaningless, but are taken as an invocation of (or an appeal to) 84 bodhisattvas and other deities, each of which is illustrated; the illustrations are of some quality, and are followed by an illustration of Weituo (韋陀 or 圍陀), the guardian of Buddhist scriptures and libraries, which is often postfixed to works of this kind.

There are two interesting illustrations at the front of this section (the first two leaves of the whole book). The first is of what Blofeld (p.128) calls the “visualisation” (meaning mental picture) that one should have in one’s mind when reciting the mantra Oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ (an ma ni ba mi hong 唵嘛呢叭彌吽), moving with each syllable from the heart, through the left shoulder, the throat, the right shoulder, and the navel, to the head, so that one’s body, speech, and mind are transformed into the body, speech, and mind of Guanyin.

The second illustration is of the thousand-armed Guanyin, who is conventionally depicted with 42 arms, each of which holds one of the instruments of salvation.

The second appendix

This is an illustrated account of these 42 instruments, the words being derived from scripture, as evidenced by the introduction to each explanation with the words 「經云 …」 . A search of the Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association’s (CBETA) full-text database suggests that the sutra whose words most closely match both these, and the words of the Dabeizhou in the first appendix, is 《千手千眼觀世音菩薩大悲心陀羅尼》 (Taisho Tripitaka 大正新脩大藏經 vol.20, no.1064).

Not only have I so far found no other copy of this edition, but I have not even found any pre-modern edition at all with the title 《大悲懺儀合節》, with the single exception of an edition that was auctioned in Peking in 2011 and which is clearly from different blocks, being described as 「清咸豐五年[1855]易居齋刊本」. But the text of the main part and its appendix seems so basic that it may have been published with other titles. I’m hoping that readers with a greater knowledge of this subject will tell me.