In October last year Chris Fletcher drew my attention to an early Chinese missionary printing block advertised for sale in a catalogue of mostly western books which I would not normally have seen, and I bought it immediately. It is now in the Library, shelfmarked Sinica 6002.

The bookseller was Samuel Gedge (Hanworth, Norwich), and his Catalogue XIV says that “the Chinese text, identical on both sides, includes a translation of the Lord’s Prayer in the version of the missionary Robert Morrison (1782-1834).” (no.59, p.46).

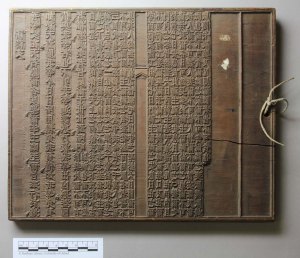

Here is an image of what I call “side A” of the block, as it bears a western inscription written with pen and ink, now very faint, and discussed below:

The block has been cut on both sides, as blocks usually are, but it is curious that on this block the text is identical on each side apart from the very minor differences noted below, the two extra punctuation marks on “side B”. The text is indeed that of the Lord’s Prayer, and it is followed by that of the Ten Commandments, and nothing else. Here is a transcription of it:

祈禱文

吾等父在天者、愿爾名成聖、爾宰王臨至、爾旨奉行於地、如於天焉。賜我等今日日所用糧。免我負債、如我等免負債與我等者也。不引我等進誘惑、乃救我等出凶惡。葢國者、權者、及榮者、皆屬爾、于世世焉、啞門。[1]

除我外、爾不可有別神也。爾不可為自而造何雕刻的像、或天上之何像、或於地下、或於水在地之下也。汝不可自俯伏向之、並不可事之、蓋我神主、爾神、乃忌被忽之一位神、而問父之罪及子輩、於恨我者之三四代也、乃施慈憐於愛我者、守我命者、之于萬人也。爾不可徒然而用神主爾神之名、蓋徒然而用、厥名者、將不算其人為無罪也。記憶撒吧日、以守之聖然。六日間、爾可勞而行汝諸工、但第七日乃神主、爾神之安息日、在之爾不可行何工、連爾、與爾子、爾女、爾僕、爾婢、爾牲口、及在爾門內之客皆然。蓋六日內神主造天、地、海、及凡在伊內、[2]且於第七日安息、故此神主祝福安息日、而聖之。○ [3] 敬爾父、[2]爾母、致爾各日可為長多於神主爾神給爾之地。爾不可殺人。爾不可姦人妻。爾不可偷人物。爾不可言妄証及爾隣也。爾不可貪爾隣之家、爾不可貪爾隣之妻、厥僕、厥婢、厥閹牛、厥驢及凡屬爾隣者、皆不可貪也。

[1] The columns of the Lord’s Prayer are widely spaced.

[2] The two punctuation marks 、 here are only found on side B.

[3] This circle divides the first four commandments (concerning God) from the last six (concerning others).

So far, I haven’t found the text of either the Lord’s Prayer or the Ten Commandments exactly as it appears on this block in any of Robert Morrison’s works. But it comes very close, and certainly much closer than the text of any other versions.

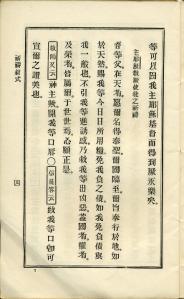

I have compared the text of the Lord’s Prayer with the versions in Matthew 6:9-13 and Luke 11:2-4 in the first two editions of his New Testament (1813 and 1815, noted in my previous blog entry). I have also compared it with the version in the little prayer-book which according to Milne (Retrospect , 269) he produced in 1818, although our edition of this only raises more problems (it appears to be an experimental edition, containing only the first part of the text, and is at variance with the descriptions in Milne’s Retrospect, Wylie’s Memorials, and other catalogues). But here, for what it’s worth, is my catalogue entry for it, together with an image of the page on which the Lord’s Prayer first appears:

年中每日早辰祈禱之敘式

[s.l.], [s.a.]

平裝1冊(12頁) ; 18.5公分

Running title 《祈禱敘式》

Tr. by R Morrison

Printed on single leaves of western paper

Has no title-page

Sinica 2511

Similarly, I have compared the text of the Ten Commandments with the versions in Exodus 20:1-17 and Deuteronomy 5:4-21 of Morrison’s Old Testament (completed in 1823 with the assistance of William Milne), and it comes very close to the text of the Exodus account.

Morrison was active in Canton and Macao, but our block was cut in Java, according to the inscription on Side A. This is very faint, and not easy to read, so we took it to the Papyrology Room of the Sackler library where it was subjected to multispectral imaging by Alexander Kovalchuk, who uses the technique to enable ancient papyri to be read. Monochrome images of the object are taken with light of different wavelengths, ranging from infrared through the visible spectrum to ultraviolet; the images are then digitally processed using complicated mathematical algorithms. Here is what emerged when the process was applied to the block:

I’m reading this as follows: “Chinese Blocks cut at Waltefreden at the Missionary station in Java. Bennet.”

As ever in this game, each additional piece of information raises more questions than it answers: where are the other blocks, and who is Bennet?

But first, I must acknowledge the help of my former colleague Ralf Kramer in solving the problem of “Waltefreden” (which at first I had found impossible to read). It is actually an anglicisation of Weltevreden, a wooded, swampy place 12km southeast of the old city of Batavia (now part of modern Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia).

As its name suggests, the European colonists found Weltevreden to be a more pleasant place to live than the old walled city of Batavia, which was dirty and overcrowded and suffered from bad sanitation. According to an article in The Jakarta Post (Saturday 19 February 2000), in 1797 the Dutch colonial authorities started to turn it into an administrative and military area. Soon after, Herman Willem Daendels, governor-general of the Dutch East Indies from 1807 to 1811, selected the site for his residence and also for the new city centre.

Also, the blogger P’i-kou has pointed out that it was in his residence at Weltevreden that Daendels established the first printing press in Batavia, around 1810. Medhurst’s mission and its press however were based not in the governor’s residence, but in Parapattan, so that the reference on the block is to the general area in which Parapattan was located, not the governor’s press.

Turning to the block itself, there is something odd about it. I’ve already noted that the text is almost absolutely identical on both sides, but also, neither side has ever been inked – the block has never been used to make an impression. The format is also puzzling. The text appears in a frame, as if intended to be a leaf of a book rather than a “sheet” tract. But neither the title nor collation details appear where they would normally be in the central column of the block, which is completely blank. I wonder if the block was produced as a specimen, to show what a Chinese block looked like, and how leaves were printed and bound to make books? And perhaps more than one of these specimens was produced.

It is hard, but essential, not to be led astray by wishful thinking. This is why I hedged my bets with dating our copy of the earliest Chinese tract (also by Morrison) in my previous blog entry. But there’s nothing wrong with putting something up for others to shoot down – this is surely partly what a blog is for.

As indicated in the inscription, the missionary station in Java was in Batavia, and Walter Henry Medhurst was in charge of it. Medhurst was born in 1796, and at the age of 14 was apprenticed to a printer. In this capacity he replied to an advert by the London Missionary Society for a printer to join their mission at Malacca (now Melaka on the southern coast of the Malaysian peninsula, half-way between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore). He was accepted, and on the way there “entered into a matrimonial alliance” as Wylie deliciously puts it (Memorials, 25) – fast work, which surely lays to rest any notion that the missionaries might be boring! He reached Malacca in 1817, and was ordained there in 1819. Having spent a year in Penang in 1820, he moved to Batavia for the next eight years. There, as in Malacca, a major part of his work was in setting up a printing office.

In Journal of voyages and travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, esq. Deputed from the London Missionary Society, to visit their various stations in the South Sea islands, China, India, &c., between the years 1821 and 1829 (London, 1831), the entry for 22 August 1825 (vol.2, 223-224) gives a detailed description of the process of blockprinting, which was observed in “Mr Medhurst’s office”.

I wonder if our block was produced for Bennet to show to the London Missionary Society when he got home?