What to call this blog entry was solved by an article in last week’s Independent (Tuesday 9 July 2013, 28-29) by David McNeill. Presumably the author found the image on the internet – I think I’ve found the one he used, which appears in numerous locations, and is rather good.

The article concerns the Senkaku Gunto 尖閣群島, the uninhabited group of rocky islands situated in the East China Sea between Taiwan and Okinawa. I give the islands their Japanese name because the Japanese are currently their internationally accepted owners, backed by American interests in the area. They are however claimed by the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan, who know them as the Diaoyu islands 釣魚島 or Diaoyutai 釣魚臺.

The positions of all the claimants, together with their arguments, are set out comprehensively in the Wikipedia account of the dispute. And an interesting piece by Daniel Dzurek, written some while ago but rich in detail, is to be found here.

For sure, Diaoyutai is the earliest recorded name of the islands, and the reason the matter finds itself in this blog is because by an extraordinary coincidence, the first textual references to them appear in two documents of entirely different provenance in the Bodleian Library.

Both texts were discovered by Xiang Da (Hsiang Ta 向達) during his stay in Oxford from November 1935 until December 1936, which had been arranged by Yuan Tongli (Deputy Director of the National Library of Peiping), E.R. Hughes (recently appointed Reader in Chinese Philosophy and Religion at Oxford University), and Edmund Craster (Bodley’s Librarian) to enable him to catalogue the Library’s Chinese collections. Xiang Da’s stay in Oxford has been documented by Frances Wood in a recently published memorial volume for him (敦煌文獻‧考古‧藝術綜合研究 : 紀念向達先生誕辰110周年國際學術研討會論文集 / 樊錦詩, 榮新江, 林世田主編. – 北京 : 中華書局, 2011. – ISBN 978-7-101-08337-8). The original English text of her account can be seen here.

Xiang Da’s work in the Bodleian is particularly important for at least two reasons.

Firstly, he set up the first Chinese card catalogue in the Bodleian, and as described by Frances Wood, it was constructed along very sound lines which other libraries at the time would have done well to follow. I was still adding to this catalogue until it was closed in 1991, when automated Chinese cataloguing began.

And secondly, he wrote a lengthy article on the Bodleian’s historic Chinese collections, albeit with a few errors, in the journal of Peiping Library (as the National Library of China was then called) which introduced them to a wide audience in the Far East, and is still used to this day (瀛涯瑣誌 – 記牛津所藏的中文書, in 北平圖書館館刊 10:5, 1936, 9-44).

It is here (pp.30-33), I think, that the two rutters were introduced to sinology (and to politics) for the first time, although at the time the article was written, the ownership of the Diaoyu islands was not much of an issue, so there was no reason to mention to them, any more than to mention the numerous other locations referred to in the texts.

Twenty-five years later, Xiang Da published an account of the texts, with full transcriptions of them:

兩種海道針經 / 向達校注

北京 : 中華書局, 1961

平裝1冊(277頁) : 圖, 地圖 ; 18公分

(中外交通史籍叢刊)

附地名索引

統一書號 11018.142

As a result, the rutters became widely known in the Far East, and in recent years, they have become available on the internet in various locations.

Less freely available are original images of the texts, which have only just been made. It is planned to make them available in their entirety from the Serica interface in the near future, but for the convenience of those who might be interested in this matter right now, in a moment I will show scans of the four places (two in each text) where the mentions of Diaoyutai occur. But first, a few notes on the texts themselves.

The first is the so-called Laud rutter, described as follows in my catalogue:

順風相送 : 不分卷 / (明)佚名撰

明抄本

洋裝(原線裝)1冊 ; 26公分

MS.Laud Or.145

The title by which this book is known, Shunfeng xiangsong, appears only on its cover. It is undated, but Xiang Da strongly suspects that it was produced in the 16th century (p.4).

The ultimate Chinese provenance of the book is not known, and strange as it may sound, it hasn’t even been established how Laud got his hands on it. Xiang Da suggests that it came from “a European Jesuit university” (歐洲一所耶穌會大學), and indeed most of Laud’s manuscripts were of continental origin.

We know from western inscriptions on the book that it came into the Library in 1639:

and also that it was examined by Shen Fuzong and Thomas Hyde in 1687:

The second text is appended to a small collectaneum of military works, which as indicated by its shelfmark, is part of the famous Backhouse Collection which came to the Library in stages between 1913 and 1922:

兵鈐 : 內書八卷外書八卷 / (清)呂磻, (清)盧承恩編

附 指南正法 : 不分卷 / 佚名撰

清康熙乙卯[1675]序鈔本

線裝7冊 : 圖 ; 30公分

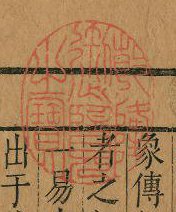

有「曾存定府行有恒堂」印記

Backhouse 578

This collectaneum never seems to have been printed, and although several manuscript copies of it are in existence (there is one complete copy and two incomplete copies in Peking University Library, another in Nankai University Library, and an incomplete copy in Princeton), only the Backhouse copy contains the vital appendix.

This seems to confirm Xiang Da’s view that although the preface to the book is dated 1675, our copy was actually written out rather later at the end of the Kangxi period, when the appendix was added.

I have only recently transcribed the single seal impression on the Backhouse copy, which informs us that it was formerly in the ownership of Zaiquan 載銓 (1794-1854), the fifth Prince Ding 定郡王, a great-great-grandson of Gaozong, the Qianlong Emperor. This I learned from a discovery on the internet, which even led me to the very bronze seal from which the impression was made, together with the help of Zheng Cheng 郑诚. If only identifying seals and their owners were always so easy! In view of the evanescence of things on the internet (to which I have referred before), for the sake of posterity, I have preserved the web-page in question here.

And here are the images of the passages concerning the Diaoyu islands. The leaves were originally unpaginated – my references are to the pencilled foliation done locally some decades ago.

順風相送, 13a:

順風相送, 62a-63a:

指南正法, 7b:

指南正法, 33b-34a:

Inevitably, I learned about these texts at a very early stage of my career, when my interest in our historic collections was developing in the late 1970s. But I did not know about the Senkaku Islands, nor the fact that their ownership was in dispute, until I received a letter from Kazuyoshi Umemoto, Second Secretary in the Japanese Embassy in London, dated 18 August 1981. The letter asked us to show Shunfeng xiangsong and any other related documents to Professor Toshio Okuhara, a specialist in international law and an authority on this matter. In the event, I don’t think Professor Okuhara ever came; I think it was Mr Umemoto himself, and he must have come at the approach of winter, because he had a pair of elegant leather gloves which he laid carefully on the desk before examining the manuscript. It is odd how irrelevant little details like this stick in one’s mind while one forgets more important things.

It may not be a coincidence that at the end of 1982, a year after Mr Umemoto’s visit, a second printing of Xiang Da’s book was produced. What had not been an issue in 1961 had clearly become one since, as evidenced in some small but significant changes to the text.

In glossing the island Huangweiyu 黃尾嶼 (p.168,n.1), the changes are as follows:

1961: 黃尾嶼為今尖閣群島之久場島. (“Huangweiyu is the present Kubashima in the Senkaku Islands.”)

1982: 黃尾嶼為我國臺灣省所屬島嶼. (“Huangweiyu is an island which belongs to our country’s Taiwan Province.”)

And in the place-name index (p.253) the entries for the alternative names of the islands have also been modified:

1961: 釣魚嶼 — 釣魚嶼為自臺灣基隆至琉球途中尖閣群島中之一島, 今名魚釣島, 亦名釣魚島. (“Daioyuyu — Diaoyuyu is one of the Senkaku Islands which lies on the way from Jilong in Taiwan to the Ryukus; its present name is Yudiaodao, and it is also called Diaoyudao.”)

1982: 釣魚嶼 — 釣魚嶼在臺灣基隆東北海中, 為我國台灣省附屬島嶼, 今名魚釣島, 亦名釣魚島. (“Diaoyuyu — Diaoyuyu is in the sea to the northeast of Chilong in Taiwan, and is an island belonging to our country’s Taiwan Province; its present name is Yudiaodao, and it is also called Diaoyudao.”)

1961: 釣魚臺 — 此指琉球群島中尖閣群島之魚釣島, 一般作釣魚嶼, 亦作釣魚臺. (“Diaoyutai — This refers to Yudiaodao in the Senkaku Islands in the Ryukus, and it is commonly called Diaoyuyu or Diaoyutai.”)

1982: 釣魚臺 — 此指臺灣基隆東北海上之釣魚島, 一般作釣魚嶼, 亦作釣魚臺. (“Diaoyutai — This refers to Diaoyudao in the sea to the northeast of Chilong in Taiwan, and it is commonly called Diaoyuyu or Diaoyutai.”)

Most recently, in September 2012, in a further attempt to cement their claim to the islands the Chinese published a large and detailed map of “The Peoples Republic of China’s Diaoyudao and associated islands” (ISBN 978-7-5031-7131-4); I remember buying a comparable map of the Falkland Islands in 1982 – how else was one to know where they were?

Apart from Mr Umemoto, to my knowledge the only other diplomat to examine the Laud and Backhouse manuscripts is Dr. Shen Lyushun, the Taipei Representative in London, who visited us on 30 November 2012.

I don’t know if any representative of the Chinese government has ever examined the manuscripts in the flesh, but some years ago a student told me he had been asked to look at them on their behalf.

By way of a postscript: it is ironic that Xiang Da, who discovered the documents which are now being seen by some as favouring his country’s claim to the Senkaku Islands, should have perished as a class enemy during the Cultural Revolution – and in that I suppose his visit to Oxford didn’t help. He was sent to labour in the countryside, and having a weak heart, died there almost immediately in 1966.